“I have come to the conclusion that much can be learned about music by devoting oneself to the mushroom”- John Cage

Introduction

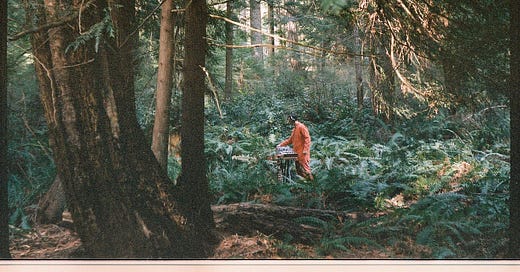

Hi! My name is Tarun Nayar. You may know me as Modern Biology on the internet. I’m a biologist and musician and love making music with plants and mushrooms. The most common questions I get are ‘How does this work?’ or ‘How can I do this?’. This guide is my attempt at putting all of my thoughts and learnings into one place. My goal? To empower you to explore this world of nature, sound and vibration with me.

Trees are sanctuaries. Whoever knows how to speak to them, whoever knows how to listen to them, can learn the truth. They do not preach learning and precepts, they preach, undeterred by particulars, the ancient law of life.- Herman Hess

How it works

‘Plant music’ or ‘mushroom music’, as it’s most often made, is not complicated. With a little guidance, anyone can learn and anyone can do this. I often liken it to a grade 6-level science project. I’ll get into the specifics below, but the most common approaches involve comparing various measures for ‘bioelectric activity’ over time. Bioelectricity is the electrical activity in living organisms. As any being lives and grows, its bioelectric field changes. These fluctuations can be converted into note and rhythm changes on a synthesizer. Voila! ‘Plant music’.

FIRST, AN IMPORTANT NOTE ON ‘PLANT MUSIC’

Plants don’t make music. Let me say that again. Plants don’t make music. Plants do make sounds though. Scientists at Tel Aviv University have shown that tomato plants emit high frequency clicks above the range of human hearing (40-80 KHz) when stressed. There’s also evidence of lower frequency sound emissions along the elongation zone of root tips of corn. Some researchers argue that these sounds are just incidental - the result of physical processes inside the plants such as cavitation (when air bubbles form inside plant tissue). Others believe these sounds are used in communication. And there is strong evidence to show that plants can ‘hear’, with one experiment by Monica Gagliano and her lab at Southern Cross University showing that growing pea shoots can grow towards the sound of water. There is increasing evidence that fungi, too, respond to sound, with results indicating that high frequencies may inhibit mycelial growth and spore production, while low frequencies can stimulate growth (turns out mushrooms like bass - big surprise).

However, these plant and mushroom sounds and the science of plant bioacoustics are not what we’re talking about in this guide. Rather, we’re using electrical fluctuations in plants and mushrooms to trigger note and rhythm changes on a synth. We’re collaborating with the natural environment in what I find to be a very enjoyable and meaningful way. But these plants and mushrooms are not singing.

“It is inaccurate and unethical to answer the question How do plants sound? by transposing vegetal processes onto musical scales and producing “the music of plants.” If we truly heed the phenomenological injunction “Back to the things themselves!”, we will have to listen to - and hear - the things themselves, without drowning their voices in ideal harmonies.”- Monica Gagliano

History

Humans have been communicating directly with plants and the natural world for thousands of years. The Mestizo Shamans of the Upper Amazon undertake rituals like ‘dietas’ to communicate directly with the spirit of plants through song and visions. Kathleen Harrison remarks that in this tradition “Every species has a song. If you are granted the song in a vision state, or by just submitting yourself to the presence of a plant and opening up, then it’s a real gift, and you are able to remember that song forever and share it when it seems appropriate. …They are part of an encyclopedia on the sonic level of the same thing that seeds represent on another level.” I believe that these and other indigenous ways of knowing are vital for the future health of our planet. I hope that the techniques in this book can act as a gateway to learning more about how humans can come into direct communication with the natural world.

The Celts believed a tree’s presence could be felt more keenly at night or after a heavy rain, and that certain people were more attuned to trees and better able to perceive them. There is a special word for this recognition of sentience, mothaitheacht. It was described as a feeling in the upper chest of some kind of energy or sound passing through you. It’s possible that mothaitheacht is an ancient expression of a concept that is relatively new to science: infrasound or “silent” sound. These are sounds pitched below the range of human hearing, which travel great distances by means of long, loping waves. They are produced by large animals, such as elephants, and by volcanoes. And these waves have been measured as they emanate from large trees. - Diana Beresford-Kroeger

In the foreword to The Immortality Key, author Graham Hancock shares that the Mazatec shamans of southern Mexico refer to psilocybin mushrooms as "little teachers," and suggests that all psychedelic plants and fungi can be seen as "literally the ancient teachers of mankind." He believes that these organisms are doing more than communicating with us - throughout the ages they’ve been our teachers and have awakened us to our spiritual potential.

Electricity and Plants

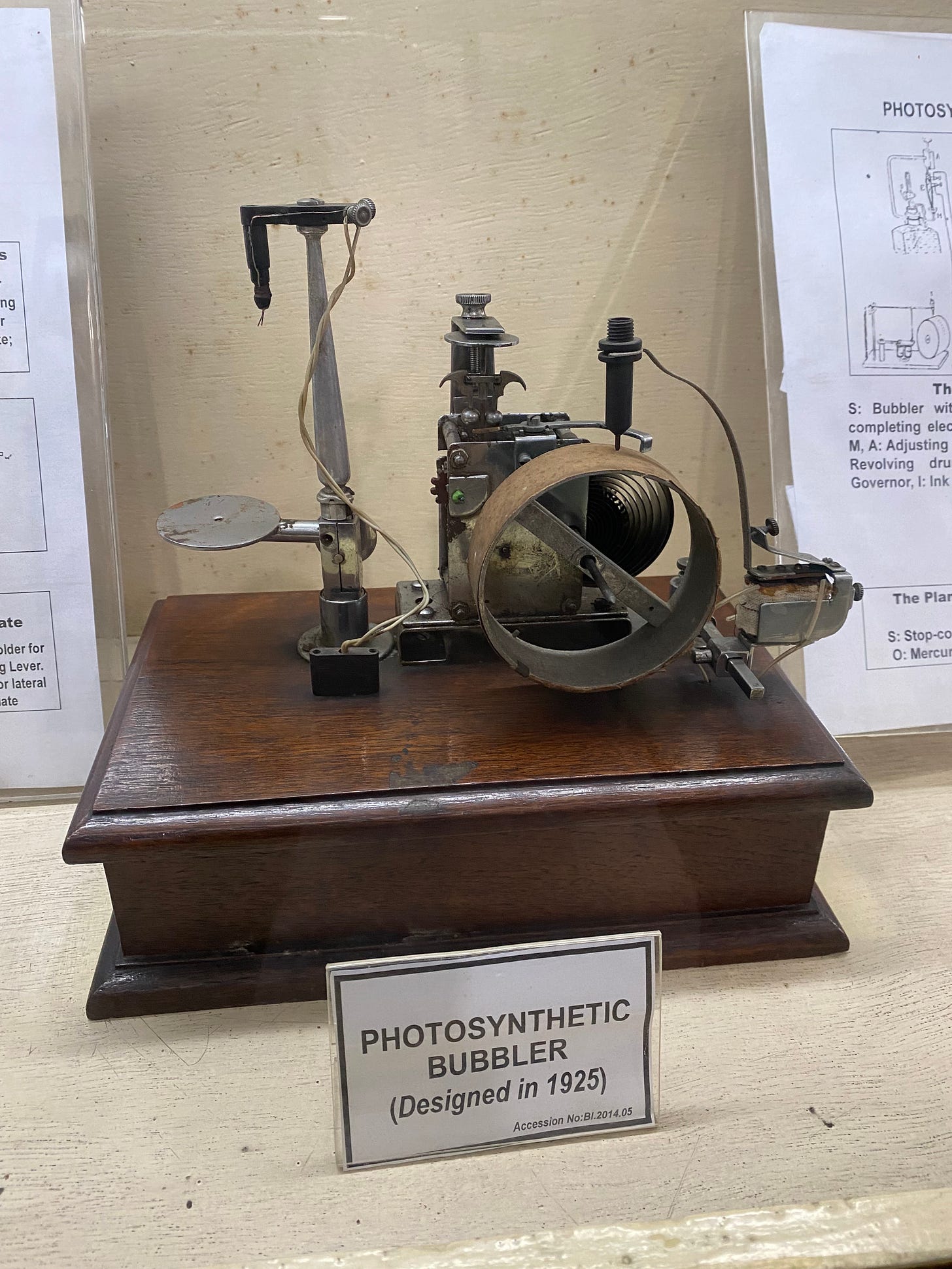

Western science has been exploring electricity in plants for over 150 years. In the 1870s the British physiologist John Burdon-Sanderson found that the carnivorous venus flytrap plant’s predatory movements were caused by electrical action potentials in its leaves - similar to how movement is created in animals. Flies land on the leaves, an action potential is fired, the trap closes - the fly is eaten! Indian scientist Jagdish Chandra Bose devoted much of the early 1900s to the study of ‘plant neurobiology’ - investigating the electrical and nerve-like behaviour of plants. Originally controversial, this field has matured and resulted in hundreds of scientific publications. In his recent book, Planta Sapiens, Paco Calvo points out nerve-like electrical signaling happens across all kingdoms of life - and the presence of ‘expensive’ chemicals like auxin (similar to seratonin, dopamine and adrenaline) and melatonin in plant signaling pathways indicates nervous and emotional systems in plants analogous to those in humans.

Butterflies don’t write books, neither do lilies or violets. Which doesn’t mean they don’t know, in their own way, what they are. That they don’t know they are alive - that they don’t feel, that action upon which all consciousness sits, lightly or heavily. Humility is the prize of the leaf world. Vainglory is the bane of us, the humans. - Mary Oliver

What the Heck is ‘Bioelectricity’?

At 22 days a single cell jolts to life. This first beat awakens nearby cells, and incredibly, they all begin to beat in perfect unison. These beating cells divide, and become your heart. This desire to beat in unison seemingly fuels our entire lives - from the movie Alive Inside

Call me biased, but I think the study of bioelectricity is one of the most important fields of scientific research today. In her book We Are Electric, Sally Adee defines bioelectricity as ‘the natural electrical processes and phenomena occurring in living organisms, driven by ion flows and electrical fields.’ This can include everything from nerve activity, to the development of embryos along electrical gradients, to the coordination of tissue movements. There is very little that happens in our bodies that is not in some way regulated by electricity. And some researchers argue the electrical gradient between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ in early cell-like structures was the key ingredient in the origin of life 4.2 billion years ago.

It’s hard to believe that until the late 1700s, Western science didn’t even know that our bodies were electric. It took two dueling Italians - Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta - a couple of decades of dissecting frogs and electrocuting dead human bodies to convince the scientific community that the human nervous system operates using electricity. And it wasn’t until this century that the true magnitude of these electrical systems became a little clearer.

Every movement, perception, thought is controlled by electrical signals. Every single cell of the body is a little electrical battery, shuttling ions through its membrane - Sally Adee

Ion currents in our cells control cell membrane voltage. And membrane voltage determines what tissue these cells organize to make, as cells change their identities depending on electrical cues from their neighbors. So electricity isn’t just used for communication. The electrical properties of our cells determine what they become. What groups of cells, or tissues become. And ultimately what WE become. Our DNA may control what proteins we’re making in the cell. But electrical information is controlling what happens to these proteins - how our cells and tissues grow and occupy space in a 3 dimensional world.

Michael Levin, a biologist at Tufts University, calls bioelectricity ‘cognitive glue’. His research indicates that electrical fields allow groups of cells to organize, coordinating the behavior of individual cells into a unified, functional system, much like how cognitive processes integrate information to produce coherent thoughts or actions. Or individual birds coordinate to form a flock. He posits that all intelligence is collective intelligence. He challenges us to see ourselves as a bag of neurons - and these neurons give the impression of behaving like ‘one’ thing - like an ant colony. Levin argues that there is no real ‘central nervous system’ and that the notion of a distinct cognitive entity is not backed by any evidence. Instead, we have a colony of individual cells organizing themselves via electrical gradients into a seemingly coherent entity called a human being. Or a plant, or a mushroom.

In the last several years we’ve seen some fascinating studies that explore some of the ways plants and mushrooms use electricity. In 2022, researcher Adam Adamatzky and his team published a paper looking at electrical spiking behaviour in 3 species of mushrooms and used linguistic analysis to suggest that these signals might be acting as a kind of ‘fungal language’. In 2023, Japanese researchers examined a cluster of Laccaria bicolor mushrooms after a rain, showing more evidence of fungal communication via electrical signaling. And two of my favorite scientists - Monica Gagliano and Adam Adamatzky - recently showed that spruce trees in a forest synchronized their bioelectric activity during an eclipse, with older trees actually anticipating the eclipse! Here we have a number of separate individuals integrating themselves into a coherent entity through bioelectric activity. So cool!

‘Modern’ Plant Music

Most of what is now called ‘plant music’ involves translating the electrical activity of plants into musical compositions. My first encounter with this idea was through a fascinating video called ‘The Singing Plants of Damanhur’. Since the 1970s, members of the Damanhur spiritual community in Italy have been exploring plant-human relationships, developing devices that enable people to create music with the electrical changes in plants.

This approach has roots in the work of Cleve Baxter, featured in the opening chapter of the iconic book The Secret Life of Plants. Baxter conducted experiments in the 1960s using modified polygraphs (or lie detectors) to measure electrical activity in plants. He claimed that plants responded to harm inflicted on themselves or others - even at a distance - suggesting they possessed a kind of extrasensory perception. While his work caught the public’s attention, it was met with strong backlash from a scientific community that was not quite ready to entertain the possibility of plant sentience.